A-D

E-H

I-N

O-R

S-T

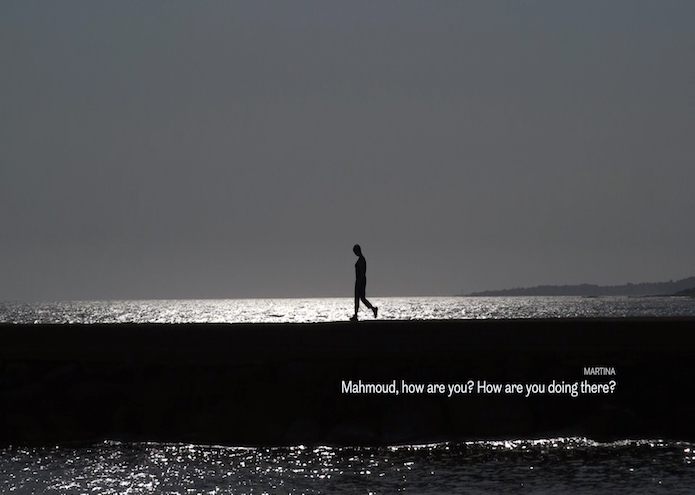

Filming in her grandparent’s home near Padova in Italy, Martina identifies a map of places belonging to their past. Antonio was born in Libya when it was an Italian colony and lived in Tripoli where he married Narcisa. They were suddenly forced to leave the country in 1970 just after Gheddafi’s coup d’etat. With the help of a young Libyan contacted on social media she collects images of her grandparents ‘home’ town today. Some names have changed, others not. As they exchange pictures and chats their relation grows. The web allows them to slowly overcome the physical and cultural boundaries that separate their lives, bringing us into a world the media has no access to.

Italy / 66 min.

Directed by: Martina Melilli

Produced by: Stefilm

In association with: ZDF, Arte, Rai Cinema

With the support of: Mibact, Piemonte Doc Film Fund, Regione Piemonte

DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT

I believe in the value of individual stories that can tell what is shared by many, in the choral quality of a story that collects its many different shades and points of view. All the Italians who lived the experience of the forced exile from Libya in 1970 share the story of my grandfather Antonio. The story of Mahmoud is the one of a young generation that has to grow, study, become an adult in a country without a specific identity, divided by violence and economical interests, that has to find a way towards its future in all that chaos. What these two have in common is the city of Tripoli: the first lived there in his past, the second lives there today; both of them consider it their “home”. The private and individual details make these stories unique. I studied in Venice –where I got a degree in Visual Arts- and Brussels – where I studied documentary and experimental cinema. Traveling is a part of me and of my job as visual artist and filmmaker. The representation of –individual and collective-memories and the role of images and the media in our contemporary society, together with the concept of “belonging” and the question on what home is, are at the core of my artistic research. The three of us (my grandfather, Mahmoud and me) share a present time in which we try to compare ourselves, to give each other some answers, to find our place in the world. When thinking back to their golden times in Tripoli, the word my grandparents use most often is “fraternity”. This is what they miss most since they got to Italy: the sense of community that characterized their life there; feeling part of a bigger something. Even if he is very young, Mahmoud has already lost this sense of community in his land. And will I ever find it? Where? How? Or, maybe, with whom?

Mahmoud is a nuclear engineering student, who in the meanwhile got his degree. We meet through Facebook and he decided to help me find the traces of my grandparent’s past: he filmed with his smartphone from the windshield of his car the places belonging to my grandfather’s memory. In the months, now years, our digital-epistolary relation became a true friendship. We never met in person yet, we never even spoke: we just write to each other. We chat. This also gives a sense of protection in which one feels free to expose oneself, free from the other’s gaze, from a real shared intimacy. Eventually, if one of the two stops replying it is as if the whole thing never existed: vanished into thin air. And this is what I’m afraid of: that all of a sudden he could vanish, leaving me unable to understand if something is happening to him or if he simply decided not to reply anymore. Our exchanges are nourished by images and stories, and make us slowly and always deeper discover who “the other” is, our daily lives, our dreams and ambitions. The differences are a lot, beside the obvious ones related to gender and to geographical-cultural diversity. For instance, cinema has a fundamental role in my life, as the need of travelling, the movement. All realities that Mahmoud doesn’t know: he has never moved from Libya, where public transport does not exist, the airports have been destroyed or occupied by the militias and the Islamic State. All the cinemas of Tripoli have been closed or banned, and he has never been into one of them. Maybe just once, but he was a little child, and doesn’t remember it. Nevertheless, we are both looking for who, what, and where we will be “tomorrow”. What is home, where is “home” to be built?

The socio-political situation of Libya doesn’t seem to get any better. On the contrary, it appears suspended on a constant, stagnant, tension that seems to be more tending toward an involution than towards the conflict’s resolution. All of this is less and less spoken about. It’s like the entire world is waiting, silently. Waiting for what, though? This wait is devastating. Mahmoud often mentions the option of taking one of those boats that many choose as an escape route. This really scares me a lot. I try to make him understand that the risk is too high, that that is not a solution. But he says he has nothing to lose.

Towards the end of the film, my grandfather looks out of the window, his only porthole on the world, looking towards an undefined elsewhere. Does he think of the past? Is he imagining the future? “Good things come to those who wait”, he tells me. “And what are you waiting for, grandpa?” I ask him. “I don’t know” he replies. And neither do I. But yes, I wait.